Not in Kansas anymore

Okay, let’s talk food. There wasn’t any. I was being fed through a nasogastric (NG) tube; the tube that went from my nose down into my stomach. I needed this because the medical team were unsure if my swallow was affected by my surgery, and the tracheostomy would also make eating more difficult. I hadn’t even been allowed to swallow water; if I was thirsty, they would allow me to take some juice into my mouth and then they would suction it back out. I couldn’t even taste it. The cold alone was delicious, but the frustration was maddening. Inevitably they could not suction it all and I would swallow some. This minute rebellion was surprisingly beneficial to my morale- it was a tiny victory against my fictitious jailer. Score: Ed- 1, unrelenting savagery of the universe- several thousand and counting. There came a time when they checked if I could swallow effectively. How? By putting a camera up my nose to peer down my throat like an over eager tonsil fetishist. This is about as comfortable as you’d imagine. So, there I was; one nostril with a feeding tube, one with a camera with an (admittedly lovely) lady asking me to swallow. I was actually swallowing a mouthful of expletives; but if this is what I had to endure for a burger then so be it. Thankfully I was given the all clear. Eventually I was allowed to eat ice cream; my visitors quickly caught on and regularly supplied me with Twisters from the hospital shop.

I am now an expert in having my teeth brushed. It’s on my CV. Apparently there are only two ways to brush someone else’s teeth. You are either someone who gently and tentatively caresses them as if you’re dusting down the family china, or you could scrub the entire inside of the mouth like it owes you money; teeth, cheeks, tongue- the whole 9 yards. It got to the point I could assess with alarming accuracy someone’s technique just by how they gripped the toothbrush. Daintily: might as well not bother. With a closed fist: even my baby teeth in dentistry heaven are going to feel this. May my gums rest in peace.

There is something unavoidably degrading about not being able to look after yourself, to suddenly not even be able to manage your personal hygiene. I guess that’s why it’s called personal; there’s something invasive about handing it over to somebody else- even something as small as brushing your teeth. It’s an assault on your dignity. Over time I think your dignity re-forms into a new shape, like roots around rocks- you have to be open to the process, and be ready for change. It requires letting go, and that requires time.

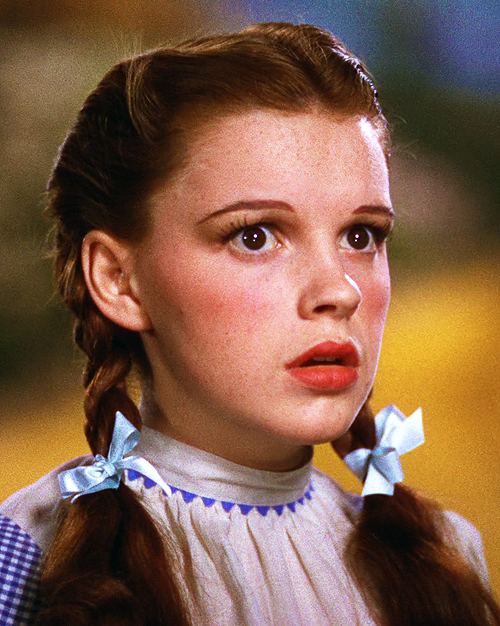

There was something almost imperceptible about how the staff treated me that let me know I wasn’t in a winning category. Later on, there was talk of mouth painting and wheelchairs, which I was not in any way ready to take on board; the thought of being wheelchair dependent disgusted me. The weakness of my body disgusted me. My inability to heal disgustedly me too. I just wasn’t ready. After just a few weeks I was still in denial, desperately holding onto the Ed of before, not knowing that he was already dead. In one way I was mourning him, deeply and profoundly aware of what had gone and was not coming back. In another way I was him, alive, strong and ready to overcome the situation I was in. Sometimes this dichotomy of looking forwards and looking backwards felt like it was tearing me apart. I wasn’t in Kansas anymore. Something about this photo of Dorothy really resonates with me; the combination of fear and uncertainty, the deep trepidation in her face really mirrors how I remember feeling.

I felt like a sponge, laid in bed slowly soaking up the harsh reality I was steeped in, swelling up with it. Over time it was weighing me down and I was sinking. As I gained more strength and more time passed, I had more resources to devote to assessing my situation: it wasn’t good. I knew that with every day that I wasn’t improving my odds of improving were dwindling. I was itching to work to improve, but there was nothing I could do but agonisingly wait for something to change, each day that nothing switched back on was another day standing still. In that respect every day was a disappointment. I would stare my hands and for hours a day and I would try to bring each of my fingers to my thumb one after the other over and over and over again. The tragic thing was that if I didn’t look it would feel as if they were moving, but every time I would check and be able to see my hands they would lay there, lifeless. In the fleeting tatters of sleep, I would have recurring dreams of sitting alone in some desolate landscape just opening enclosing my hands; then I would wake up and sometimes be cursed with a few moments where I would forget that any of this had happened. Realisation would rush into me like a dam had broken: the rushing water was putrid, sewage. After a few weeks my left bicep woke up in an otherwise comatose arm. The bicep was hardly wide-awake; it would just twitch and almost imperceptibly bend my arm, but that didn’t matter: it was hopeful. Sadly, there would be no more waking up after that.

Sometime into my intensive care stay I got moved to a quieter part of the unit as they anticipated that I would be there for some time. This area had huge windows that I could see out of- even when laid flat. This was March 2018 and huge snowstorm was ravaging Nottingham and most of the UK around that time. This did a couple of things. Firstly, it made it extremely difficult for people to visit me. In hindsight I’m not sure that that was necessarily a bad thing; it gave everybody a legitimate excuse to take some time for themselves. The second thing that it did was send my world another layer deep into some sort of surreal fever dream. I remember vividly listening to The Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad in between episodes of fitful sleeplessness, whirling swathes of snow passing the windows, centring me in a vortex of white on a stark background of the night-time darkness. With my headphones on I couldn’t hear the many beeps and whirrs of the machinery keeping me alive, and the lights of the ward were sleeping. The loneliness was so stark it was almost comforting. I was in another world. I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

So much of the world around me was passing me by and I was unaware. I was in the midst of that blizzard and couldn’t see the wood for the trees, or the sky for the snow. I didn’t know the suffering that was going on around me; how could anyone expose me to their difficulties when objectively things were worse for me? I was sovereign in the land of despair. Only months, years later did I begin to understand. Some days Izzy was more upset than others. One of those days she had had to go back to my flat to retrieve some of my things. She had seen my calendar on the wall, days ticked down in anticipation of a holiday together. Days neatly ticked down up to February 15. She had been encouraged to go back to work only a few weeks after my injury to see if that would help her cope, give her some structure, some distraction. She returned to work on neurosurgery as a junior doctor; unsurprisingly some neurosurgery patients are in intensive care, and her work would include seeing patients on ITU. That’s right, the same place I was. She would go to work and be expected to perform her job while being maybe metres away from where I was battling to breathe. Doctors work so hard to help and support people but so often overlook each other. A full exposition on the state of professional relationships in healthcare will wait for another time, but I’m sure medical professionals will read this and may well be saddened or outraged on her behalf, but probably not surprised. Relationships with staff on the ward were sometimes strained as the boundaries between Izzy as a professional and as grieving partner was sometimes blurred. This was so not only with Izzy but with many of my junior doctor friends who would come and see me in their lunch break or after work. I couldn’t see from their point of view. So much was going on outside of my ITU bubble that I only gradually became aware of much later.

At some point during my early weeks in intensive-care there was talk transferring me to the Sheffield spinal unit. Getting off the ventilator was vital; the wait for ventilator beds at Sheffield could be months and months, whereas being transferred once off the ventilator could be much faster. This only fortified my will to improve in what little ways I could; I was told the spinal unit could offer specialist rehab catered for my specific injury and would be the place for me to translate my will into recovery. At the same time talk of the next few months was jarring; I was meant to be finishing my first year as a doctor in a few months, I had other plans which weren’t meant to include a long stint of inpatient rehabilitation. It was hard to hide from myself the fact that those plans had been replaced, that that calendar was in an alternate universe now.

Another powerful and very articulate blog post. Thank you Ed for sharing these with us and please keep it up!.

X

Very raw and emotional, but at times also humorous. Never stop writing!

I’m proud of you.

Man, this post really stands out. Reading it I can really imagine this time some of what you went through and eventually mastered. It made me scared, sad, relieved, hopeful, not once or twice and not in lineal order.

What Im now wondering, however, is can anyone rebuild themselves after so tragic an event; Mentally, physically, like you have? Like you still will? Smooth seas and sailors aside, you, Ed have always had that incomparabile tenacious spirit within you. I’ve known that always in you, and I don’t think you’d be this far without your granite Will.

Loving these posts anyway Dawg, hope to see you soon when I’m back in the Uk and enjoy a twister together for dam sure. 😂

Much love brah x

Really moving blog Ed, it’s so well written thanks for sharing your story x

Another moving Blog – such courage and will.