Oh, how the breakers roar

Keep pulling me farther from shore

Thoughts turn to a love so kind

Just to keep me from losing my mind

So enticing, deep dark seas

It’s so easy to drown in the dream

Breakers Roar – Sturgill Simpson

So, let’s talk about the tracheostomy. The word tracheostomy comes from trachea: your windpipe, and stoma: mouth, or hole. So, I had a hole in my neck. My little neck hole; like My Little Pony but for adults in critical care. Now as cruel as doctors can be, they don’t just put holes in people for no reason; that’s more common practice with Mexican drug cartels or the KGB, and as far as I know neither of those run the QMC ITU. So, I needed a neck hole because I needed to be ventilated, and the ventilator could either get to my lungs conventionally, i.e. through my mouth, or less conventionally via a tracheostomy. As you can imagine, having a big plastic tube in your mouth and down your throat tends not to be very comfortable; so uncomfortable that people are usually put to sleep so they can tolerate it. I sort of needed to be awake to crack on with my life, so neck hole it was- not that I really had a choice.

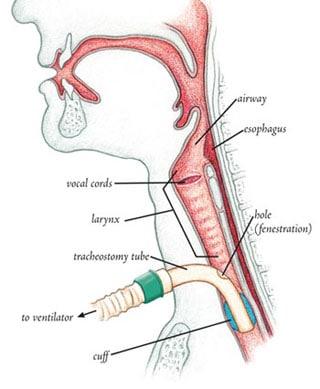

So, once you have your lovely little neck hole, a plastic tube is mounted in it so that other things- like a ventilator or other equipment- can be attached to it. In order for the ventilator to work the air it pushes through the tracheostomy needs to go down into the lungs, and the air it sucks back out needs to come out of the lungs too. The problem is that if you just put a tube into someone’s neck and attach the ventilator, the air you push in will go both down into the lungs and up and out through the nose and mouth, which is no good. This is prevented by the tracheostomy tube having a balloon on it that is inflated once the tube is in place; this balloon is referred to as the cuff. Cuff up: balloon inflated. Cuff down: balloon deflated. If you’re feeling lost, I’ve included a handy diagram.

With the cuff up the tube is anchored in the trachea and the balloon blocks any flow of air up to the mouth; the ventilator only has access to the lungs. Now we are directing traffic. This is all well and good, but without any air coming up your trachea and out of your mouth, no air is passing through your vocal cords: you cannot speak. So I had a choice: ventilator or talk. It’s a fiddly situation; you can see why drug cartels tend not to be known for managing complex airways.

So I could only mouth words and make weird hissing sounds like an asthmatic snake for the first few weeks in intensive care; this combined with not even being able to scratch my nose obviously sucked harder than Noo-Noo on heavy stimulants. One problem was my skin; the combination of illness, the air-conditioning of ITU and my constant face-to-face relationship with the ceiling (always horizontal) meant that the skin on my face dried into cornflakes at an alarming rate. You don’t realise how much skin you make -and redistribute by just moving around- until you stop moving altogether. These cornflakes weren’t destined for the breakfast bowl of a bright-eyed teen looking to take on the world; they were destined for trouble. Whenever I would cough, be turned, or just move my head or face a little too much, that skin ended up in my eyes. Not a day went by when I wasn’t intermittently blinded by my own exfoliation, and then had to try and mouth for someone to irrigate my eyes so that they would stop burning and I could see again. Sadly, this was just one skirmish in the war my body would wage upon itself, upon me. The battles continue today, I just lose less often. That episode was one of my first tastes of the bitter, agonising helplessness I still intermittently find myself in. That frustration is one of those emotions that is very hard not to reflect back yourself and impotence can so easily turn into self-loathing: “Why am I the way that I am? Why am I so pitiful, so useless?”

Oh, how the breakers roar

Keep pulling me farther from shore

Thoughts turn to a love so kind

Just to keep me from losing my mind

So enticing, deep dark seas

It’s so easy to drown in the dream

Breakers Roar – Sturgill Simpson

Thankfully, it wasn’t long before I found my voice. After a few weeks of slowly strengthening my breathing doing longer and longer stints with the ventilator turned off, there was talk of seeing if I would tolerate having the cuff down. So rather than my lungs having to suck air through my neck hole, the neck hole would be plugged off and I would breathe through my nose and mouth, just as God intended. Although you might think there’s not much difference, the distance from my mouth to my lungs is longer than from my neck to my lungs; this makes the task much harder, like having to suck through a longer straw- and in the state I was in at the time, that extra distance turned a molehill into a mountain. So instead, there’s a thing called a passy muir or speaking valve. It’s a cap for the tracheostomy with a valve that allowed me to breathe into my neck (easier) but breathe out through my mouth; and if I could breathe out my mouth, I could talk. I actually still have my speaking valve today, as gross as that is.

Now, there’s one last bit of boring neck tube science to cover. Remember those secretions I’ve talked about before? So, they’re still hanging around, like youths at 11pm. With the cuff up any secretions from above will slowly accumulate, flow down the trachea, and pool on top of the tracheostomy. Not that much fluid forms above the cuff, and while the cuff is inflated it’s no problem; it can’t go anywhere. However, when the cuff was deflated to allow me to speak that pool of secretions just became a waterfall; without anything to hold the gunk back it would all fall at once. Have you ever tried to snort a booger rather than pick your nose, to be rewarded (or punished) with a bit of snot breaking the sound barrier as it zooms up your nose and back down your throat? If you haven’t, you’re missing out on absolutely nothing. If you have, this was quite similar; just as parking your car in the driveway is similar to piling an articulated lorry through your house.

The result was I would cough and retch really hard for maybe 10 minutes and then I would be in the clear. I remember how distressed it made my visitors; I was used to coughing and retching and respiratory distress, but normally it was with the privacy of closed curtains and a physio or a nurse- the people around me were usually shielded from the worst of that. Now if they wanted to speak to me -and I to them- we had to do this uncomfortable dance, with me sounding like I was trying to invert my lungs and them attempting to act like this was perfectly normal.

So finally, I could talk. I actually can’t remember what my first words were, but they were probably pretty caustic and not very inspirational. I had forgotten what I sounded like. Before the cuff came down for the first time there were jokes with the nurses about how they expected me to sound; posh or not, baritone or soprano. I think the first people I spoke to were my parents, but it might have been Izzy. I remember how oddly normal the conversations were, like we were sitting on the sofa at home or had met up for coffee; on a little island and the sea was raging. I mean, what do you say? “Hi, my life is ruined- so how’s work been?” All of a sudden, I didn’t have to mouth and spell things out with a whiteboard full of letters, but I didn’t have the words. I don’t think anyone else did either. Maybe I was on the island by myself. I had spent so many days stuck in my head, so many conversations had been stilted or killed by my inability to speak, so much frustration and anguish and madness, but I couldn’t get it out. I had so many voices in my head, but none in my mouth.

Talking was physically really hard. I had one muscle to do all the work and it wasn’t in the best shape: the first time I think I managed half an hour. Once I had the freedom of being able to express myself and be understood, even if it was just banal conversation, I loathed becoming tired and having to go back to the ventilator. The doctors had to limit my time with the speaking valve on so that I didn’t exhaust myself and ruin my progress. But now the carrot on the end of the stick was so much sweeter; every minute of progress breathing solo translated to more strength and therefore, more talking. I can’t really describe how transformative that first step was; being even slightly sat up, seeing the walls, looking people in the eye and speaking to them- it turned me from an amoeba to a man. Just having the air flowing through my nose and mouth meant my sense of taste was resuscitated. My life had gone from black-and-white to sepia tone, even if I was too confused to express how I felt.

Flashing forward to today; the hole in my neck has healed (spoilers) and I can talk for as long as I like- you can ask the people around me if that’s a good or a bad thing. I really wasn’t sure what to title this post- calling it something like tracheostomy would be really dull and not capture what it’s about. When rereading this post, I realised that I’d used the word neck a whopping 14 times and this, and everything else, all comes back to my neck in the end. The photo is the rear scar from my initial surgery; sometimes I get mad that it healed so well- it doesn’t do the severity of the injury justice, but at least it looks pretty.

Thanks for reading. Please go to the homepage and subscribe if you’re interested in getting updates when I post new stuff. Comments are always appreciated.

Amazing Ed.

We have followed your progress vis Tom Fish and his family

Ed, I think your blogs are quite witty in the face of adversity. I’m glad to read that there is improvement (being able to speak!) Also the diagram of your tracheostomy – gives an insight as to what really is involved (for you) and it’s not nice (but necessary). Glad to hear it’s gone and that ‘hole’ has now healed

You are a very inspiring person and I look forward to reading your next blog.

Another beautifully written post. Particularly enjoyed the unexpected link to Noo-Noo on YouTube haha

Hi Ed

Great blogs! very witty and insightful. I learnt so much about spinal cord injuries from working with you. Keep up the amazing work and all the best going forward.

Hi Ed being a nurse I find you blog particularly interesting – in how you have and are adapted to your new life, I’m sure you could write a book and I look forward to reading your next blog.

Amoeba to a Man. Black and White to Sepia tone. But at all stages colourful and intelligent